Thermodynamic Principles of Metallurgy :

`=>` Thermodynamics help us in understanding the theory of metallurgical transformations.

`=>` Gibbs energy is the most significant term here.

`=>` The change in Gibbs energy, `ΔG` for any process at any specified temperature, is described by the equation :

`ΔG = ΔH – TΔS` .................(14)

where, `ΔH` is the enthalpy change and `ΔS` is the entropy change for the process.

For any reaction, this change could also be explained through the equation:

`DeltaG^(⊖) = - RTln K` .........(15)

where, `K` is the equilibrium constant of the ‘reactant-product’ system at the temperature,`T`.

`=>` A negative `ΔG` implies a `+ve` `K` in equation 15. And this can happen only when reaction proceeds towards products.

`=>` From these facts we can make the following conclusions :

● When the value of `ΔG` is negative in equation 6.14, only then the reaction will proceed. If `ΔS` is positive, on increasing the temperature (`T`), the value of `TΔS` would increase (`ΔH < TΔS`) and then `ΔG` will become –ve.

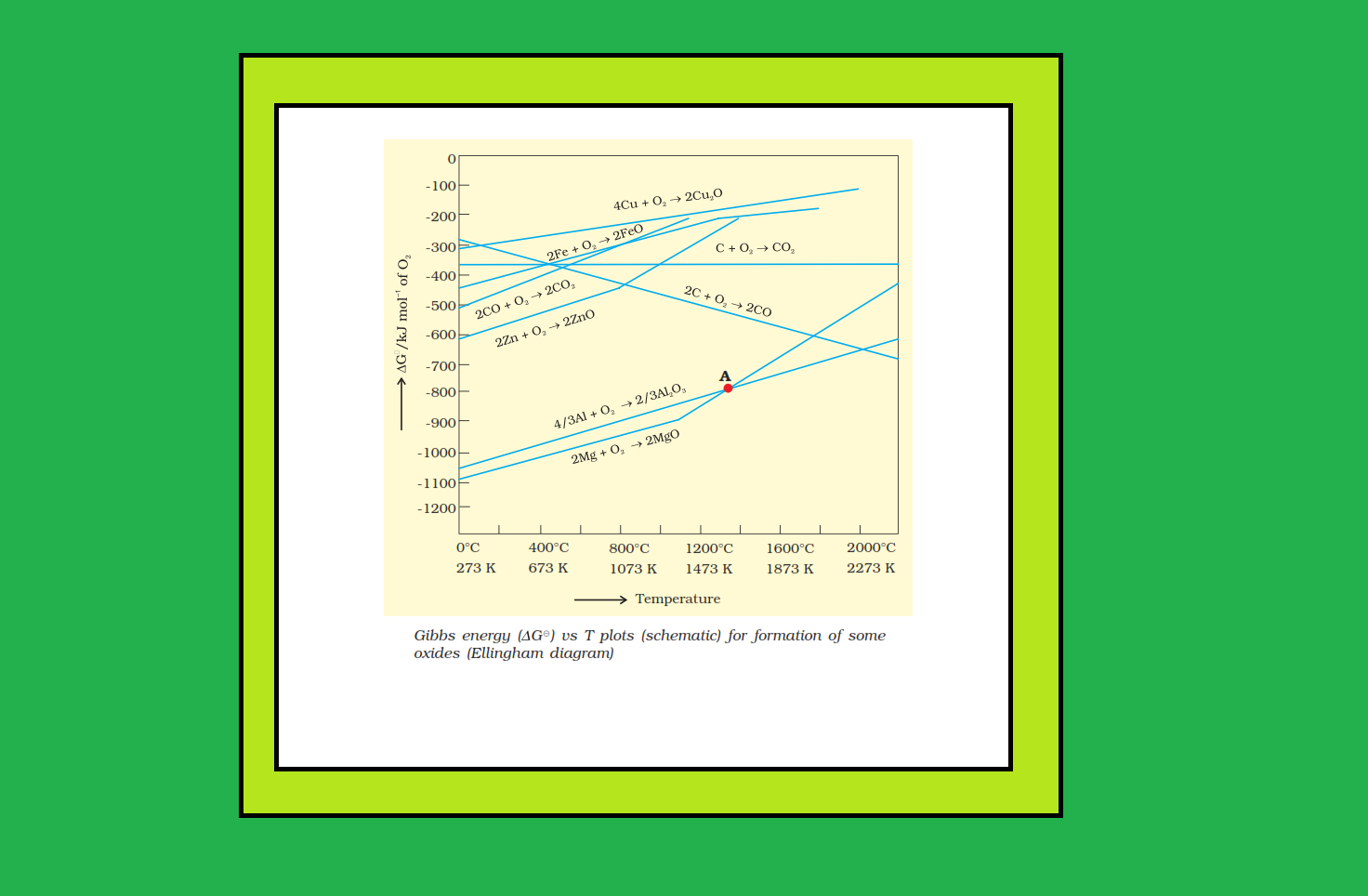

● If reactants and products of two reactions are put together in a system and the net `ΔG` of the two possible reactions is `-ve`, the overall reaction will occur. So, the process of interpretation involves coupling of the two reactions, getting the sum of their `ΔG` and looking for its magnitude and sign. Such coupling is easily understood through Gibbs energy (`ΔG^(⊖)`) vs `T` plots for formation of the oxides (Fig. 6.4).

`=>` The reducing agent forms its oxide when the metal oxide is reduced. The role of reducing agent is to provide `ΔG^(⊖)` negative and large enough to make the sum of `ΔG^(⊖)` of the two reactions (oxidation of the reducing agent and reduction of the metal oxide) negative.

As we know, during reduction, the oxide of a metal decomposes :

`M_x O (s) → x M (text(solid or liq) ) +1/2 O_2 (g)` .............(16)

`=>` The reducing agent takes away the oxygen. Equation 6.16 can be visualised as reverse of the oxidation of the metal. And then, the `Δ_f G^(⊖)` value is written in the usual way :

`xM (s & l) +1/2O_2 (g) → M_x O(s) \ \ \ \ \ [ DeltaG_(M , MxO)^(⊖) ]` .......(17)

`=>` If reduction is being carried out through equation 6.16, the oxidation of the reducing agent (e.g., `C` or `CO`) will be there :

`C(s) +1/2 O_2(g) → CO (g) \ \ \ \ \ [ DeltaG_(C , Co)]` .........(18)

`CO(g) +1/2 O_2 (g) → CO_2 (g) \ \ \ \ \ \ [ DeltaG_(Co , CO_2)]` .............(19)

`=>` If carbon is taken, there may also be complete oxidation of the element to `CO_2` :

`1/2C(s) +1/2 O_2 (g) → 1/2 CO_2 (g) \ \ \ \ \ \ [ 1/2 DeltaG_(C , CO_2)]` ...........(20)

`=>` On subtracting equation 6.17 [it means adding it's negative or the reverse form as in equation [16] from one of the three equations, we get :

`M_xO (s) + C(s) → xM( s or l) + CO(g)` ......(21)

`M_xO (s) +CO(s) → x M(s or l) +CO_2 (g)` ...........(22)

`M_xO (s) +1/2 C (s) → x M( s or l) +1/2 CO_2 (g)` .......(23)

`=>` These reactions describe the actual reduction of the metal oxide, `M_xO` that we want to accomplish. The `Δ_rG^(⊖)` values for these reactions in general, can be obtained by similar subtraction of the corresponding `Δ_f G^(⊖)` values.

`=>` Heating (i.e., increasing `T`) favours a negative value of `Δ_rG^(⊖)`.

`=>` Therefore, the temperature is chosen such that the sum of `Δ_rG^(⊖)` in the two combined redox process is negative.

`=>` In `Δ_rG^(⊖)` vs `T` plots, this is indicated by the point of intersection of the two curves (curve for `M_xO` and that for the oxidation of the reducing substance).

`=>` After that point, the `Δ_rG^(⊖)` value becomes more negative for the combined process including the reduction of `M_xO`.

`=>` The difference in the two `Δ_rG^(⊖)` values after that point determines whether reductions of the oxide of the upper line is feasible by the element represented by the lower line. If the difference is large, the reduction is easier.

`=>` Gibbs energy is the most significant term here.

`=>` The change in Gibbs energy, `ΔG` for any process at any specified temperature, is described by the equation :

`ΔG = ΔH – TΔS` .................(14)

where, `ΔH` is the enthalpy change and `ΔS` is the entropy change for the process.

For any reaction, this change could also be explained through the equation:

`DeltaG^(⊖) = - RTln K` .........(15)

where, `K` is the equilibrium constant of the ‘reactant-product’ system at the temperature,`T`.

`=>` A negative `ΔG` implies a `+ve` `K` in equation 15. And this can happen only when reaction proceeds towards products.

`=>` From these facts we can make the following conclusions :

● When the value of `ΔG` is negative in equation 6.14, only then the reaction will proceed. If `ΔS` is positive, on increasing the temperature (`T`), the value of `TΔS` would increase (`ΔH < TΔS`) and then `ΔG` will become –ve.

● If reactants and products of two reactions are put together in a system and the net `ΔG` of the two possible reactions is `-ve`, the overall reaction will occur. So, the process of interpretation involves coupling of the two reactions, getting the sum of their `ΔG` and looking for its magnitude and sign. Such coupling is easily understood through Gibbs energy (`ΔG^(⊖)`) vs `T` plots for formation of the oxides (Fig. 6.4).

`=>` The reducing agent forms its oxide when the metal oxide is reduced. The role of reducing agent is to provide `ΔG^(⊖)` negative and large enough to make the sum of `ΔG^(⊖)` of the two reactions (oxidation of the reducing agent and reduction of the metal oxide) negative.

As we know, during reduction, the oxide of a metal decomposes :

`M_x O (s) → x M (text(solid or liq) ) +1/2 O_2 (g)` .............(16)

`=>` The reducing agent takes away the oxygen. Equation 6.16 can be visualised as reverse of the oxidation of the metal. And then, the `Δ_f G^(⊖)` value is written in the usual way :

`xM (s & l) +1/2O_2 (g) → M_x O(s) \ \ \ \ \ [ DeltaG_(M , MxO)^(⊖) ]` .......(17)

`=>` If reduction is being carried out through equation 6.16, the oxidation of the reducing agent (e.g., `C` or `CO`) will be there :

`C(s) +1/2 O_2(g) → CO (g) \ \ \ \ \ [ DeltaG_(C , Co)]` .........(18)

`CO(g) +1/2 O_2 (g) → CO_2 (g) \ \ \ \ \ \ [ DeltaG_(Co , CO_2)]` .............(19)

`=>` If carbon is taken, there may also be complete oxidation of the element to `CO_2` :

`1/2C(s) +1/2 O_2 (g) → 1/2 CO_2 (g) \ \ \ \ \ \ [ 1/2 DeltaG_(C , CO_2)]` ...........(20)

`=>` On subtracting equation 6.17 [it means adding it's negative or the reverse form as in equation [16] from one of the three equations, we get :

`M_xO (s) + C(s) → xM( s or l) + CO(g)` ......(21)

`M_xO (s) +CO(s) → x M(s or l) +CO_2 (g)` ...........(22)

`M_xO (s) +1/2 C (s) → x M( s or l) +1/2 CO_2 (g)` .......(23)

`=>` These reactions describe the actual reduction of the metal oxide, `M_xO` that we want to accomplish. The `Δ_rG^(⊖)` values for these reactions in general, can be obtained by similar subtraction of the corresponding `Δ_f G^(⊖)` values.

`=>` Heating (i.e., increasing `T`) favours a negative value of `Δ_rG^(⊖)`.

`=>` Therefore, the temperature is chosen such that the sum of `Δ_rG^(⊖)` in the two combined redox process is negative.

`=>` In `Δ_rG^(⊖)` vs `T` plots, this is indicated by the point of intersection of the two curves (curve for `M_xO` and that for the oxidation of the reducing substance).

`=>` After that point, the `Δ_rG^(⊖)` value becomes more negative for the combined process including the reduction of `M_xO`.

`=>` The difference in the two `Δ_rG^(⊖)` values after that point determines whether reductions of the oxide of the upper line is feasible by the element represented by the lower line. If the difference is large, the reduction is easier.