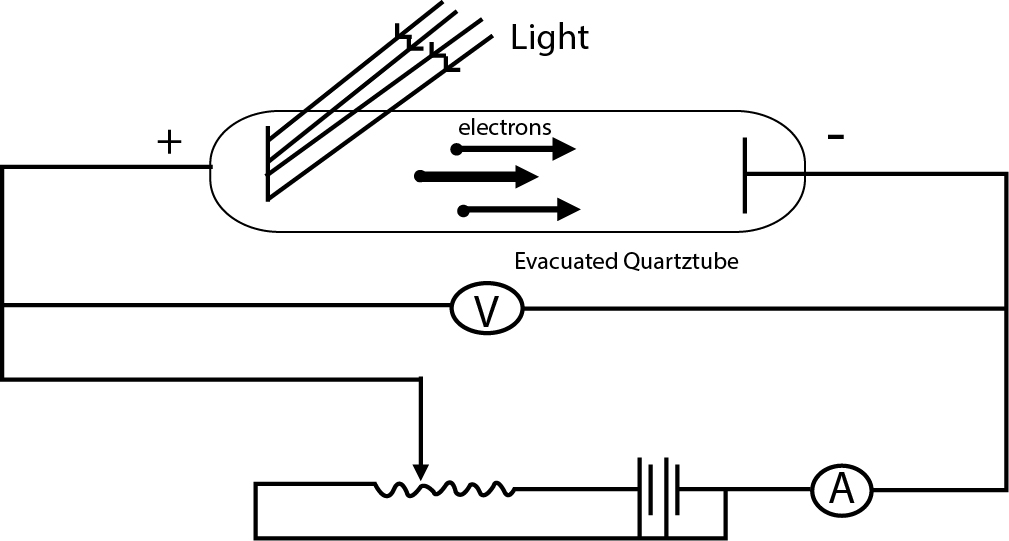

i) Electrons come out as soon as the light (of sufficient frequency) strikes the metal surface.

ii) Light of any random frequency will not be able to cause ejection of electrons from a metal surface. There is a minimum frequency, called the threshold (or critical) frequency, which can just cause the ejection. This frequency varies with the nature of the metal. The higher

the frequency of the light, the more energy the photoelectrons have. Blue light results in faster electrons than red light.

iii) Photoelectric current is increased with increase in intensity of light of same frequency, if emission is permitted i.e., a bright light yields more photoelectrons than a dim one of the same frequency, but the electron energies remain the same.

Light must have stream of energy particles or quanta of energy (`hbarnu` ). Suppose, the threshold frequency of light required to eject electrons from a metal is `barnu_0`, when a photon of light of this frequency strikes a metal it imparts its entire energy (`h barnu_0` ) to the electron.

"This energy enables the electron to break away from the atom by overcoming the attractive influence of the nucleus". Thus each photon can eject one electron. If the frequency of light is less than `nu_0` there is no ejection of electron. If the frequency of light is higher than `nu_0` (let it be `nu` ), the photon of this light having higher energy (`h nu` ), will impart some energy to the electron that is needed to remove it away from the atom. The excess energy would give a certain velocity (i.e, kinetic energy) to the electron.

`h nu = h nu_0 + (K.E)_(max)`; `h nu = h nu_0 + 1/2 xx mv^2`; `1/2 xxmv^2 = h nu - hnu_0`

Where, `nu` = frequency of the incident light `nu_0` = threshold frequency

`h nu_0` is the threshold energy (or) the work function

denoted by `f = h nu_0` (minimum energy of the photon to liberate electron). It is constant for particular metal and is also equal to the ionization potential of gaseous atoms. The kinetic energy of the photoelectrons increases linearly with the frequency of incident light.

Thus, if the energy of the ejected electrons is plotted as a function of frequency, it result in a stra ight line whose slope is equal

to Planck's constant `h` and whose intercept is `h nu_0`.

It is important to note that the expression involve `(KE)_max`. In reality `e^-` have `K.E` lesser than this.

Total energy falling on plate = `nh nu`; photon intensity = `n/(A xxt)`

Intensity of energy falling on the metal surface= `nhnu/(Axxt)`

Variation of `P. E` current vs voltage for different photon intensities `I_1, I_2, I_3`

i) Electrons come out as soon as the light (of sufficient frequency) strikes the metal surface.

ii) Light of any random frequency will not be able to cause ejection of electrons from a metal surface. There is a minimum frequency, called the threshold (or critical) frequency, which can just cause the ejection. This frequency varies with the nature of the metal. The higher

the frequency of the light, the more energy the photoelectrons have. Blue light results in faster electrons than red light.

iii) Photoelectric current is increased with increase in intensity of light of same frequency, if emission is permitted i.e., a bright light yields more photoelectrons than a dim one of the same frequency, but the electron energies remain the same.

Light must have stream of energy particles or quanta of energy (`hbarnu` ). Suppose, the threshold frequency of light required to eject electrons from a metal is `barnu_0`, when a photon of light of this frequency strikes a metal it imparts its entire energy (`h barnu_0` ) to the electron.

"This energy enables the electron to break away from the atom by overcoming the attractive influence of the nucleus". Thus each photon can eject one electron. If the frequency of light is less than `nu_0` there is no ejection of electron. If the frequency of light is higher than `nu_0` (let it be `nu` ), the photon of this light having higher energy (`h nu` ), will impart some energy to the electron that is needed to remove it away from the atom. The excess energy would give a certain velocity (i.e, kinetic energy) to the electron.

`h nu = h nu_0 + (K.E)_(max)`; `h nu = h nu_0 + 1/2 xx mv^2`; `1/2 xxmv^2 = h nu - hnu_0`

Where, `nu` = frequency of the incident light `nu_0` = threshold frequency

`h nu_0` is the threshold energy (or) the work function

denoted by `f = h nu_0` (minimum energy of the photon to liberate electron). It is constant for particular metal and is also equal to the ionization potential of gaseous atoms. The kinetic energy of the photoelectrons increases linearly with the frequency of incident light.

Thus, if the energy of the ejected electrons is plotted as a function of frequency, it result in a stra ight line whose slope is equal

to Planck's constant `h` and whose intercept is `h nu_0`.

It is important to note that the expression involve `(KE)_max`. In reality `e^-` have `K.E` lesser than this.

Total energy falling on plate = `nh nu`; photon intensity = `n/(A xxt)`

Intensity of energy falling on the metal surface= `nhnu/(Axxt)`

Variation of `P. E` current vs voltage for different photon intensities `I_1, I_2, I_3`